Discover B2B Marketing That Performs

Combine business intelligence and editorial excellence to reach engaged professionals across 36 leading media platforms.

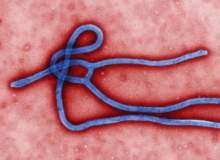

In August 2014, as the Ebola epidemic rampaged through West Africa, a handful of sufferers were offered an unprecedented lifeline. With no recognised treatment available, they received the experimental drug ZMapp, a cocktail of monoclonal antibodies that had not yet been trialled in humans. While some of them recovered, this sample size is not statistically significant and the drug’s efficacy is still unknown.

For anyone to receive ZMapp at all, it had to bypass the normal mechanisms that make up the US approvals process. The drug had been trialled on primates, but had only come a short way down the path towards approval and lacked any kind of watertight evidence base. Its use, then, was a matter of some controversy.

Under such grave circumstances, it fell to the World Health Organization to give the drug the green light. An expert panel, made up of researchers, patient safety advocates and medical ethicists, ruled that experimental interventions of this kind were justified.

Their report concluded: "In the particular context of the current Ebola outbreak in West Africa, it is ethically acceptable to offer unproven interventions that have shown promising results in the laboratory and in animal models but have not yet been evaluated for safety and efficacy in humans as potential treatment or prevention."

US Tariffs are shifting - will you react or anticipate?

Don’t let policy changes catch you off guard. Stay proactive with real-time data and expert analysis.

By GlobalDataWhile there is still no known cure for Ebola, and supplies of ZMapp have been exhausted, its rapid approval poses an intriguing question: might untested drugs prove ethically acceptable in other situations too?

New scope for untested drugs

It’s a question currently being debated in the UK, where the Medical Innovation Bill is passing through Parliament. At the time of writing, the bill has reached the Report Stage in the House of Lords, and, following further amendments to its wording, it will move on to the House of Commons.

An intriguing study, published in the August edition of the journal PAIN, has shed new light on the issue of publication bias.

"There are a lot of people with different wants and desires and needs – we’re trying to bring them together to find consensus and iron out any wrinkles," explains Dominic Nutt, director of communications for the Medical Innovation Bill.

The bill, proposed by the Conservative peer Lord Maurice Saatchi, would allow terminally ill patients in England and Wales to be voluntarily treated with untested drugs. Since losing his wife Josephine Hart to ovarian cancer, Lord Saatchi has been campaigning for the use of non-standard medicines in exceptional circumstances. The bill would give legal protection to doctors who have exhausted all other avenues and want to try something beyond the norm.

"Standard procedures are fine in 99% of cases – if you have type 1 diabetes for instance, you want evidence-based medicine, as there’s a world of research," says Nutt. "But in the case of a rare childhood cancer where there haven’t been enough patients to set up a trial, doctors want to be able to try innovative approaches. These treatments haven’t been fully tested because they can’t be, but they might do something more than the standard treatment, which we know will fail."

Nutt compares the situation to strapping on a parachute during a plane crash. Even if that parachute is labelled as untested, the alternative is inarguably worse.

Taking precautions

The bill, of course, would not give carte blanche to doctors to short-circuit normal NHS procedures. It would apply only under very specific conditions (effectively when there’s nothing else left to help the patient) and is likely to affect only a small proportion of doctors.

"Nothing in this bill excludes the standard approaches that any doctor should take, and if doctors want to do something very new and different, they should avail themselves of all the opportunities in their trust," says Nutt.

"A judge would like to see that the doctor has gone through the standard processes in order to make sure the treatment has been signed off correctly. But ultimately what we want to do is encourage a culture change within medicine. This bill gives us a means to say, ‘follow this process and you can be confident you won’t be punished in law’."

As to whether the bill may be vulnerable to abuse by unorthodox practitioners, Nutt does not believe this likely. While the WHO guidelines hold experimental treatments to a suitably high ethical standard, the Medical Innovation Bill goes one step further: it specifies that the doctor should obtain a second opinion from at least one highly qualified specialist in that field.

A crescendo of innovation

Nutt hopes to see one further amendment to the bill – the requirement that any innovative treatment be logged and registered. This would mean results can be shared with other researchers, and any patterns discerned over time might lead to a full-blown trial. While this requirement would add an extra layer of bureaucracy, the long-term benefits should speak for themselves.

He does not think that the bill will lead to a dramatic surge in experimental treatments upfront, nor that there will be a subsequent flurry of activity in court. The more likely scenario is that doctors will simply get used to using the process and that a more innovative approach to medicine may emerge further down the line. The bill, after all, is not intended to turn patients into unwitting guinea pigs, but rather to provide clarity to doctors and the legal profession.

"It think it will initially have a very gentle effect – it will percolate through slowly as junior doctors become senior doctors operating under the bill," he says. "There will be a greater sense that innovation is to be encouraged reasonably and rationally, and I think that will build to a crescendo over time."

As to how this will impact the drug approvals architecture more broadly, the long-term repercussions remain to be seen. But with ZMapp having set the precedent, it is clear that existing approvals structures around the world may be due a shake-up.

"There are many things that need to happen in the UK, the US, Canada, Europe, etcetera to help cautiously speed up the innovation process," Nutt points out. "This bill is one piece in a jigsaw."