As our understanding of human health from a holistic standpoint improves, interest in tailoring medical treatment to the needs and circumstances of individual patients has been picking up.

Discover B2B Marketing That Performs

Combine business intelligence and editorial excellence to reach engaged professionals across 36 leading media platforms.

Precision medicine, also called individualised or personalised medicine, encompasses the use of treatments and therapies that are targeted based on a specific patient’s discrete health factors, from lifestyle preferences and environmental circumstances all the way down to the sub-cellular, genomic level.

The potential of personalised medicine

Personalised medicine is an emerging field that, in conjunction with genomic advances, could herald a new frontier of preventive medicine and more targeted, effective treatments across a range of diseases. It would mark the transition between today’s system of treatment, which is a one-size-fits-all approach based on the current standard of care for the average sufferer of a given illness, and a new paradigm that takes into account the unique characteristics of the patient and even the genetic composition of the disease itself.

Early examples of more personalised treatments are most abundant in cancer care, where, in advanced health systems, patients routinely undergo molecular testing for breast, lung and colorectal cancers, as well as leukaemia and melanomas, to allow caregivers to initiate treatment

“The number of targeted therapies in the pipeline for all diseases is increasing dramatically,” American Cancer Society deputy chief medical officer J. Leonard Lichtenfeld told Genome Magazine last year. “Personalized medicine in the age of genomics means we’re living in dynamic times. The big question right now is, ‘How do we take all this new information we’re gathering and use it for the benefit of the patient?’”

US Tariffs are shifting - will you react or anticipate?

Don’t let policy changes catch you off guard. Stay proactive with real-time data and expert analysis.

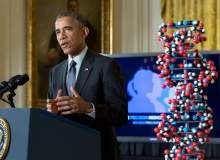

By GlobalDataHow indeed? The first step is to catalogue human health data in as comprehensive and detailed a way as possible. The widespread use of electronic health records (EHRs) and the digitising of patient information in many countries mean that this process has already started, but something bigger will be required if the immense potential of individualised healthcare is to be fully unlocked. With the Precision Medicine Initiative (PMI), launched by President Barack Obama last year with initial funding of $215m, the US is taking a leadership role in developing the concept at a macro scale.

The Precision Medicine Initiative Cohort Program

“I want the country that eliminated polio and mapped the human genome to lead a new era of medicine – one that delivers the right treatment at the right time,” said Obama during his State of the Union address in January last year. “So tonight, I’m launching a new Precision Medicine Initiative to bring us closer to curing diseases like cancer and diabetes, and to give all of us access to the personalized information we need to keep ourselves and our families healthier. We can do this.”

The key component underlying the efforts of the initiative is the creation of the PMI Cohort Program, a massive nationwide effort spearheaded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) to build a public health database that will catalogue health information, clinical data from EHRs and genomic data from biological samples.

The scale of the project is eye-catching: the PMI Cohort Program aims to enrol at least a million American volunteers, starting in autumn this year, and hitting its initial million-strong participation target by 2020. As NIH director Francis S. Collins said in July, all the future promise of precision medicine can grow from this foundation.

“This range of information at the scale of one million people from all walks of life will be an unprecedented resource for researchers working to understand all of the factors that influence health and disease,” said Collins. “Over time, data provided by participants will help us answer important health questions, such as why some people with elevated genetic and environmental risk factors for disease still manage to maintain good health, and how people suffering from a chronic illness can maintain the highest possible quality of life. The more we understand about individual differences, the better able we will be to effectively prevent and treat illness.”

Building the infrastructure of the PMI Cohort Program

Such an enormous initiative requires national and regional co-operation to match. With $55m in funding to spend in fiscal year 2016, the NIH has been doling out contracts to universities, research organisations and health centres to start building the infrastructure required to enrol such a large volume of participants and ensure that data and sample collection is done effectively.

NIH has awarded $71.6m over the next five years to Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, Tennessee to serve as the Data and Research Support Center for the project. The centre, in conjunction with partners including the Broad Institute and Verily Life Sciences, will serve as the nerve centre of the Cohort Program, organising and providing access to the massive database as it grows, as well as providing support to clinical and pharmaceutical researchers making use of the data.

Scripps Research Institute in California and Vibrent Health in Virginia will run the programme’s Participant Technologies Center, which will support direct enrolment in the PMI Cohort Program, supported by a network of Healthcare Provider Organisations, which will engage more meaningfully with local recruitment, ensuring that applicants come from suitably diverse ethnic, geographic and socio-economic backgrounds.

Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, meanwhile, will take responsibility for the PMI Cohort Program’s biobank, with $142m in funding over five years. The biobank will serve as a repository for biological samples collected under the initiative, with capacity to store more than 35 million biospecimens that can be used to drive future pharmaceutical innovation and drug development pathways.

Challenges to overcome

While it seems NIH and its partners are making all the right moves to set up a public health database of unprecedented size and scope, there are still challenges to overcome if this resource is going to find its volunteers and maximise its potential.

The human element is an outlier that could prove difficult to predict. For any precision medicine project to work there must be a strong element of patient engagement. As Collins put it, “the participants are at the table”, so ensuring that patients are compliant with data and sample collection is vital. There is strong support for the PMI Cohort Program among the US population, with a recent NIH survey of 2,600 Americans revealing that 79% of respondents supported the project and 54% would either definitely or probably contribute genetic data, biological samples, medical records and lifestyle information if asked.

Nevertheless, there can be a gulf between initial willingness and consistent engagement and the Cohort Program will have to address this. Also of concern is another result from the NIH survey that showed more reluctance to share data and samples with pharma industry researchers (52%), or government researchers outside of academia, or the NIH itself (44%).

Privacy concerns play a significant part here, as patients will expect the highest levels of data security and, as the above survey results show, they clearly have an opinion on which organisations should have access to their data. Although NIH has noted that data will be stored with “essential privacy and security safeguards”, total cyber security is difficult to guarantee in the 21st century, and in a May report the World Privacy Forum raised its own red flag.

“The key privacy concerns raised by the PMI are the lack of applicable law to govern its collection and use of individuals’ health data, the potential waiver of the patient-physician legal privilege that can shield data from disclosure through litigation, and the possibility of law enforcement access to patient records held in the PMI,” the forum noted in the report. “Before it launches, the PMI needs to clarify the legal and administrative privacy protections that apply to its activities.”

Proper regulation of genetic testing

On a legal note, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has only recently set out draft guidance for regulating the field of genetic testing in the US, which has become increasingly popular but could prove risky if the quality of such tests is inadequate.

As the director of FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health Dr Jeffrey Shuren put it in July, when the draft guidance was released: “Precision care is only as good as the tests that guide diagnosis and treatment.” Given the importance of genetic and genomic testing to some of the most valuable aspects of individualised medicine, much more regulatory certainty will be required before it can meaningfully contribute to the PMI, though there is currently no word from the FDA on when finalised guidelines will be published.

Clearly there are still many challenges to deal with as NIH starts to enrol patients and gather essential data that could drive individualised medicine and drug development. But it is equally clear that the precision medicine train has well and truly left the station; in response to the PMI, the EU is now in discussions over how to collaborate on a pan-European genomics-driven precision medicine programme of its own. “If the US can do it with a population of 320 million, surely Europe can achieve it with around 500 million citizens of its own,” said the European Alliance for Personalised Medicine in a June stakeholders update. The merit of the precision medicine has been established; as an early mover, it is now down to the PMI and its Cohort Program to lead the way.