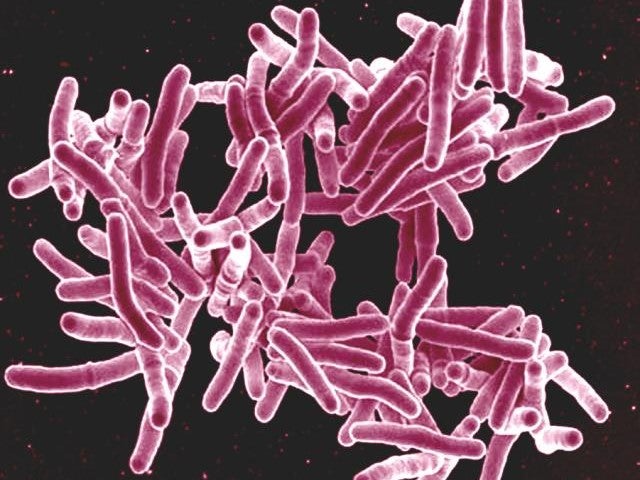

Researchers have identified group 3 innate lymphoid cells (ILC3) as the coordinators of the immune response immediately following infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb).

The researchers from Washington University School of Medicine in St Louis and Africa Health Research Institute, South Africa, have begun screening chemical compounds to find those that bolster ILC3’s activity and therefore drive a stronger, more successful immune response to TB.

Discover B2B Marketing That Performs

Combine business intelligence and editorial excellence to reach engaged professionals across 36 leading media platforms.

Interim head of department at Washington University and co-senior author of the study professor Shabaana Abdul Khader commented: “The immune response to the TB bacteria hinges on the early response of this cell, and that opens up a whole new avenue for TB control.

“Now we can start thinking about ways to target this cell to help the body fight off the bacteria before they get a chance to establish themselves.”

ILC3’s role as a master immune cell was discovered in studies of both mice and humans. Within five days of infection, ILC3 were detected in lungs where they released chemical compounds to attract and activate immune cells.

Also, mice lacking ILC3 had delayed immune responses to TB; their immune system was jumpstarted when researchers introduced ILC3 into the mice.

US Tariffs are shifting - will you react or anticipate?

Don’t let policy changes catch you off guard. Stay proactive with real-time data and expert analysis.

By GlobalDataFollowing treatment with antibiotics, ILC3 began to build up in the patient’s bloodstream, because there was no need for it to further coordinate the response.

The ILC3 belongs to an innate branch of immune cells, that have until recently been believed to have no memory. Khader noted: “It’s still an open question whether ILCs in the lung are trainable or have memory and how long the training or memory would last.

“But if we can train them and get a population of these cells primed and ready to go in the lung, that might be one way we can make a more effective vaccine for TB.”

TB vaccines have failed to prevent the spread of the disease, suggesting that adaptive immunity may be too slow. Khader explained: “We wouldn’t want to replace the Bacille Calmette-Guerin (BCG) vaccine, but we may be able to find a compound that we can use to boost immunity in vaccinated children, when the effects of the BCG start to wear off.”

Results of the study were published in Nature, which were funded in part by the US National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.