Nearly two years have passed since UK innovation foundation Nesta established the Longitude Prize as a celebration of the 200-year anniversary of the 1714 Longitude Act, which offered a £20,000 prize to anyone able to pinpoint longitude to within half a degree.

Discover B2B Marketing That Performs

Combine business intelligence and editorial excellence to reach engaged professionals across 36 leading media platforms.

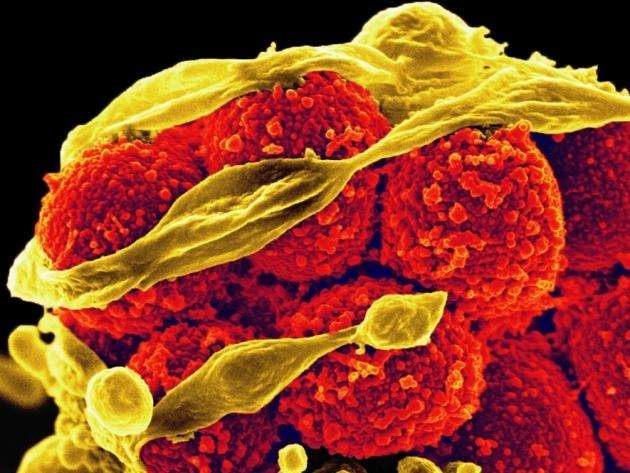

The original prize was instrumental in stimulating British innovation in maritime navigation, and its modern counterpart – a £10m prize for the development of a rapid diagnostic tool to improve antibiotic prescribing and help tackle the antimicrobial resistance (AMR) crisis – is hoping to have a similarly dramatic impact on its own field.

The Longitude Prize

A total of 206 teams have so far registered to compete for the Longitude Prize; entrants can submit their ideas in four-monthly windows, with a final winner set to be announced before November 2019. Of the 20 or so teams that have brought prototypes forward for judging, none have yet been deemed to meet the prize’s core criteria for the winning diagnostic test. While the prize can technically be claimed anytime between now and the tail end of 2019, the complexity of the challenge and the small teams involved mean the Longitude Prize organisers aren’t expecting a winning submission to emerge just yet.

“For us as a team, we’re not so surprised that, coming up to the end of our second year, we’ve not seen any [submissions] that are able to win,” says Nesta’s Longitude Prize lead Tamar Ghosh. “The experts set the [prize] term of five years with some consideration as to the amount of time it would take a novel idea to come through all of those stages of review and build through to prototype. So we’re not expecting at this stage to see the final products that are ready to win, although we are seeing some amazing ideas coming through, using gene sequencing and all sorts.”

The Longitude Prize was praised on its announcement for being one of the most significant early incentive schemes to encourage researchers to find new solutions to the AMR problem. For something like antibiotic resistance, a global public health issue that requires a multinational and multidirectional approach and which has received relatively little investment from the private sector, prize funds can play an important dual role as stimulants to innovation and loudspeakers to increase public awareness of the problem and its potential solutions.

US Tariffs are shifting - will you react or anticipate?

Don’t let policy changes catch you off guard. Stay proactive with real-time data and expert analysis.

By GlobalDataWhy diagnostics?

Antimicrobial resistance was chosen as the topic for the prize by public vote, but with so many strands of research necessary to get a grip on the problem – from developing new antibiotic classes and antibiotic alternatives to behavioural change and investigating the ways in which antibiotics are used – why did the Longitude Prize adopt diagnostics as its target?

The need for reliable, rapid diagnostic tools to help clinicians prescribe antibiotics more responsibly is beyond doubt, but financial pragmatism played a part in the Longitude Prize’s decision to lean towards diagnostics. £10m is a sizeable prize for any competition, but with drug development costs being what they are, the sum would likely not stretch far enough in some fields.

“If we think about the major areas of activity needed to tackle AMR, drug discovery is far more expensive than £10m if we’re looking at something coming to commercialise,” says Ghosh. “There’s another big chunk of work around alternatives to antibiotics, for example using bacteriophages. Again, it was felt that £10m may not go so far in that.”

A diagnostic test, with its practical utility in a range of healthcare settings, made it an appropriate subject for the prize.

“It needs to be a topic where you have an emotive link or a link that demonstrates societal benefit, so you can create the noise that’s needed to get different people into the race,” Ghosh says. “With diagnostics, there is some market interest but the diagnostics companies haven’t quite produced the kind of thing that would revolutionise this space, which is what we want to do. We’re talking about something that’s affordable, that’s usable in any health setting, that’s rapid, and can really help communities across the world, whether it’s an over-the-counter setting, a community health setting, hospital setting, or it’s around home use. That seemed to fit very well with what tends to make a prize successful.”

Diverse judges, diverse entrants

Of course, with a goal as broad as a rapid diagnostic test, it was always going to be nearly impossible to set out completely binary criteria for success, and a certain amount of subjective judgement would be required both in how the prize rules were designed and how submissions are judged.

The Longitude Prize set out clear criteria for a winning prototype, including rapid results, ease of use, accuracy, affordability and scalability. While some of the requirements are pinned down – ‘rapid’ in this case means 30 minutes from sample collection to result – others are left more open to give teams the breathing room to innovate.

“What we didn’t want to do was to design the test in advance,” Ghosh says. “We wanted to be able to stimulate innovation but not control it. [Criteria such as] accuracy, affordability and exactly how the test is used and the target infections, we didn’t want to pin down. So we deliberately let them stay open so people could decide whether it’s a respiratory tract infection test or a UTI [urinary tract infection] test, exactly how it’s going to be used and what sample is needed.”

Such an open contest requires a judging panel with the expertise and breadth of knowledge to properly assess each team’s interpretation of the brief. The prize’s judging panel includes healthcare luminaries such as UK chief medical officer Professor Dame Sally Davies, as well as microbiologists and AMR specialists, but also intellectual property (IP) experts, epidemiologists and health psychologists.

“We’ve got economists, we’ve got lawyers,” continues Ghosh. “So that cross-discipline group has the job of making those more subjective decisions, and how to weigh up accuracy with affordability and ease of use, and whether something meets the objective. So the ultimate decision for the test is: does it meet the vision of significantly reducing inappropriate use?”

The openness of the contest and the broad knowledge base of the judges – not to mention support mechanisms such as seed funding rounds and non-financial support including training webinars and connecting up talent with projects that need it – has been rewarded with a suitably diverse set of entrants.

“We’ve obviously got lots on the biology/micro-biology side, but we’ve also got lots of people from engineering backgrounds, from physics and chemistry backgrounds, and even from social science backgrounds,” Ghosh says. “We do have some teams that are coming directly from universities, from research groups or labs, but they’re in the minority. Most of our groups are combinations of researchers with industry as part of new start-ups or collaborations. Many are working across countries, so they’ve got team members from across the world. I think that’s been a really big success of the prize, that we’ve managed to encourage that as much as possible.”

Can prizes kick-start innovation?

The Longitude Prize has now been joined by a number of other AMR-focussed competitions and accelerators around the world, including the European Union’s Horizon 2020 diagnostic prize and, more recently, the US National Institutes of Health’s AMR Diagnostic Challenge and CARB-X, an accelerator with funding of $250m to spur the pre-clinical development of a whole portfolio of antibacterial products. For Ghosh, these organisations don’t represent competition, but the building of a network of funding that didn’t exist before.

“We think it’s fantastic,” she says. “For some of these, we’ve been actively involved in helping to shape them. “They’re not competing, so with CARB-X, we will try to point our registrants or teams to the other so they can make use of that if necessary, and vice versa. I would say it’s a really good network, and we talk quite regularly together. There’s so much innovation needed in this space that we need as much as we can to encourage people to enter and get involved in these.

“We’ve also seen teams that have come through the prize and because of the noise that we’re creating, along with other partners like the AMR Review, CARB-X and so forth, they’ve then found it much easier than two or three years ago to attract venture funding. So there’s a great knock-on effect, a network effect, if we have more of these prizes and other types of grants and funding available. It will not only get more innovative, but hopefully it will also stimulate more funders to consider it and support them.”

With the layered benefits of providing a new source of funding for high-risk research, boosting public awareness and potentially helping to unlock more private investment, competitions and incubators like the Longitude Prize are providing an invaluable service as the world continues to wake up to the threat posed by AMR. Whether the drugs, treatments and tools developed by the prize-winners will also revolutionise the AMR landscape remains to be seen, but the stimulating effects of these funding mechanisms are justification enough on their own.

“The private sector has a part to play, but alongside many others, and the UN General Assembly declaration last week was fantastic in getting governments to really put their hands up and say quite publicly what they’re going to do to tackle this,” concludes Ghosh, looking to the future. “Having governments leading it is just a phenomenal success, and I’m sure as a result of what Dame Sally Davies has done, and many of us working behind the scenes to try and bring this to the media’s attention. So I’m hoping [the private sector] will naturally see a market opening up, whether that’s driven by economic incentives or social incentives. That’s the hope.”