Drug affordability remains a key priority for the US government as it negotiates with pharma companies to lower individual drug prices and explore reference pricing models.

With these efforts underway on a federal level, several US states are trying to find their own solutions, including through Prescription Drug Affordability Boards or PDABs.

Discover B2B Marketing That Performs

Combine business intelligence and editorial excellence to reach engaged professionals across 36 leading media platforms.

Maryland presents a good test case for the PDAB model for several reasons. According to 2024 data, over 19% of the state’s population is employed by the federal, state and local governments, making the effects of federal agency layoffs earlier this year – and the subsequent 43-day government shutdown – particularly significant for the state’s residents.

Additionally, inflation and a higher cost of living, have made it increasingly difficult for many patients to access prescription drugs. Dr. Kate Sugarman, a primary care physician in Maryland, notes, “I can be the most brilliant doctor and prescribe all the best medicines. But if they can’t afford it, then we’re all just wasting our time.”

As the Maryland PDAB moves closer to implementing an upper payment limit (UPL) – which would cap the amount payers or purchasers, such as hospitals or pharmacies pay for a drug – it has the potential to chart the course for other states seeking to follow suit.

How Maryland plans to bring down drug prices

In April/May 2019, the Maryland general assembly passed HB 768, establishing the PDAB and outlining the conflicts of interest for members, their compensation and general structure of the Board.

US Tariffs are shifting - will you react or anticipate?

Don’t let policy changes catch you off guard. Stay proactive with real-time data and expert analysis.

By GlobalDataAt the time, the Board could set a UPL for drugs that were purchased by state hospitals, facilities and correctional facilities, state employee health plans and other programs like State Medicaid.

Approximately six years later, the state’s governor Wes Moore approved a bill that extended the powers of the PDAB to set a UPL for “payors that have led to or will lead to an affordability challenge”—thereby allowing the Board’s recommendations to apply to all Marylanders.

One lesson for other state PDABs is to not limit the target population to only state employee health plan as Maryland had initially done, says Jane Horvath, an independent health policy expert. If the Board’s recommendations apply to all residents, the state can have market leverage, especially since the process is voluntary for the manufacturer, she says.

Nonetheless, this expansion in Maryland will happen only after the UPL has been in effect for a year, when more data on the impact of the UPL can be collected.

At the forefront of the Maryland PDAB scrutiny are Boehringer Ingelheim’s Jardiance (empagliflozin), AstraZeneca’s Farxiga (dapagliflozin), Novo Nordisk’s Ozempic (semaglutide), and Eli Lilly’s Trulicity (dulaglutide). Each of these drugs has been deemed “unaffordable” in recent months, with UPLs already proposed for the first two already.

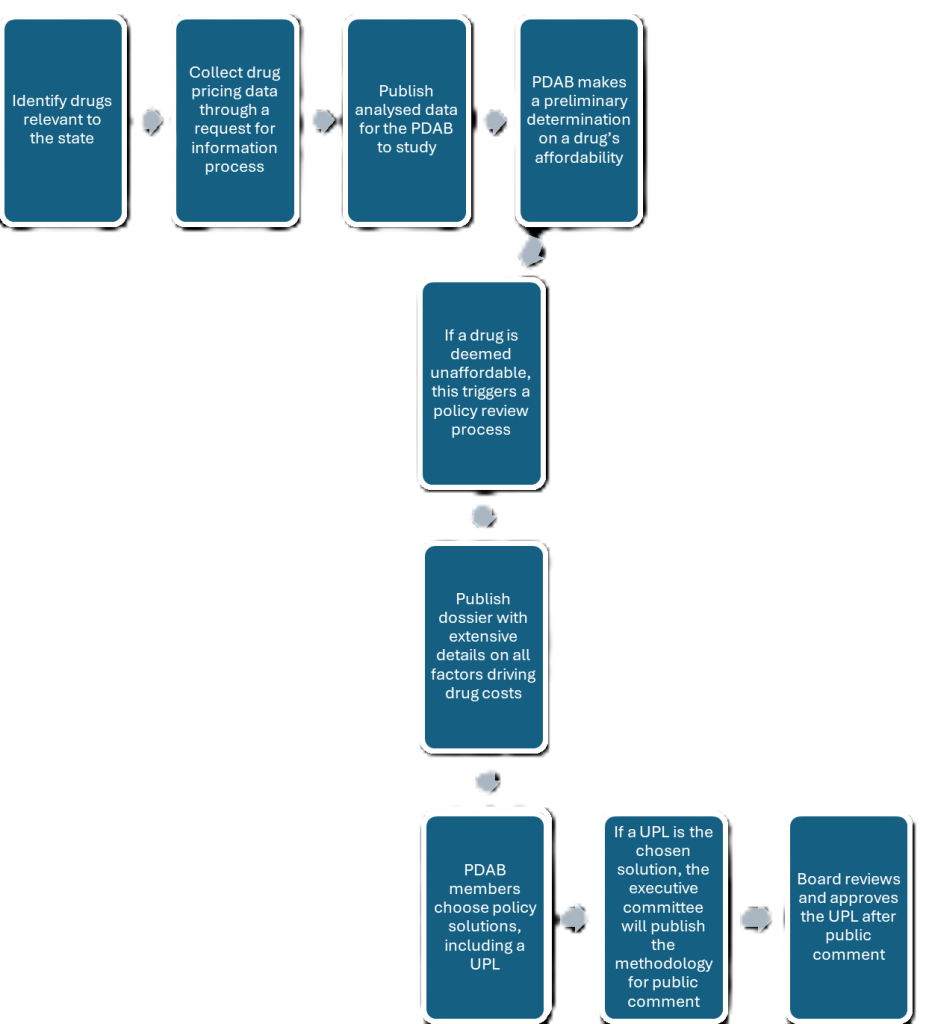

The Board made these determinations after an extended process full of public consultations and intensive reviews, which has taken a longer than anticipated.

“As an advocate, sometimes I feel like I’m feel like I’m getting impatient that it’s taken so long, but the Board is going out of its way to be fair and open and transparent,” says Leonard Lucchi, a patient advocate.

Lucchi has several connections to the Maryland PDAB. A Maryland-based lobbyist, he helped draft the proposal for the PDAB. He is also a diabetes patient on Jardiance, one of the drugs reviewed by the Maryland PDAB. As a patient, Lucchi describes his experience at the pharmacy counter, where he was presented with a drug’s cost, at times different than usual, and asked if he could afford it. He explains that this occurs because some people do not pick up their prescription after learning the price, as they simply cannot afford it.

A major challenge in finding ways to make drugs affordable is identifying what they cost to a patient. The cost of a drug to an individual patient is influenced by their insurance carrier, copayment and coinsurance rates, and discounts or rebates, which makes it challenging to collect accurate data on drug utilisation.

To address this, the board conducted review studies and accessed data that is not publicly available, says Andrew York, executive director of the Maryland PDAB.

These were then compiled into publicly available review dossiers that include different ways in which a drug’s price is analysed; as per wholesale acquisition cost (WAC), average sales price (ASP), average wholesale price (AWP), patient copays and more. Additionally, the committee members also considered the prevalence of a particular disease in the state, other alternatives to the reviewed drugs and whether the particular drug is in shortage.

If the Board considers a drug to be ‘unaffordable’, it can suggest a policy solution like, but not limited to UPLs. For the UPL route, York says, the Board would consider several ways to determine the ideal price; index pricing, reference pricing, which is being considered on a federal level through the Most Favored Nation (MFN) policy, or budget-based pricing, in addition to looking at things like a drug’s value and comparative effectiveness, says York.

Of all the frameworks to reference, York believes the Centers of Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS )’s process to implement Maximum Fair Price (MFP), under the Inflation Reduction Act, is highest on his list. Last month, the Maryland PDAB recommended using the MFP of $197 for Jardiance and $178.50 for a Farxiga, for a monthly supply of the individual drugs.

Following a public comment period on the methodology behind the suggested UPL, a critical part that has accompanied each step in this process, the Board can approve the UPL.

What will happen next in Maryland?

While the Maryland PDAB achieved several major developmental milestones in 2025, many unknowns remain. Chief among the criticism levied against the Board is the concern that any price limits will reduce access to that drug in the state, a point repeatedly expressed by patient advocacy organisations during the Board’s meetings throughout the year.

“It doesn’t strike me that if you have a UPL, it impacts access. Lower prices result in better access to pharmaceuticals,” says Gerard Anderson PhD, a Maryland PDAB member, and professor at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, in Baltimore, Maryland. Nonetheless, Anderson says the Maryland Board recognises these concerns and is trying to mitigate any adverse effects.

Dr. Benjamin Rome, assistant professor of Medicine at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, Massachusetts, cautions against extrapolating all formulary changes to state and federal policies, and to consider changing market factors. For example while looking at the price of biologics like Amgen’s Enbrel (etanercept), the fact that it is competing with biosimilars for AbbVie’s Humira (adalimumab), which are likely to be cheaper, needs to be considered, he says.

There is value in states testing their own mechanisms to bring down prices. While CMS negotiates prices for only a handful of drugs that meet certain criteria – such as having been on the market for a period of time – Anderson notes that state PDABs do not have those limitations and have the flexibility to look at expensive drugs that are not being reviewed by Medicare.

For now, the Maryland Board is moving ahead with rolling parallel processes, dependent on what policies the Board wants to implement for each drug. Notable amongst those may be a UPL for Farxiga and Jardiance after the ongoing public comment process is concluded. Anderson notes that while the Board is still in its early stages, the hope is that more progress will follow over the next several years.

This story is part of a reporting fellowship sponsored by the Association of Health Care Journalists (AHCJ) and supported by The Commonwealth Fund.