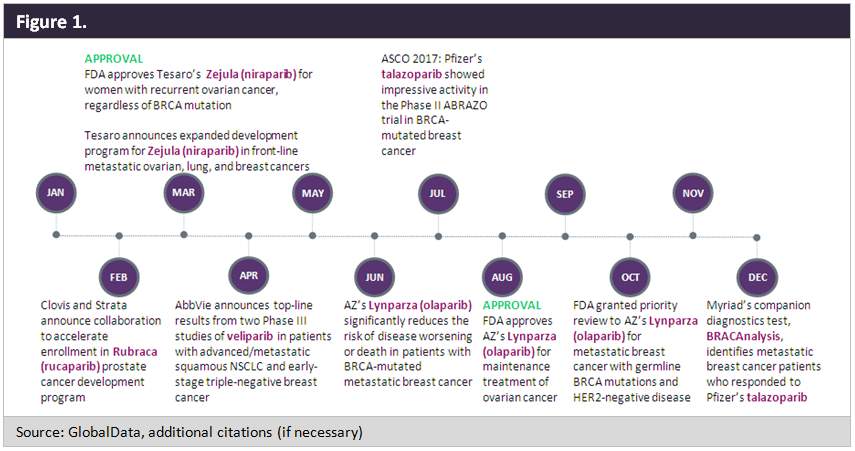

The poly ADP ribose polymerase (PARP) inhibitors market is bustling with activity, which is incontestable from a review of an action-packed 2017, shown as a timeline in Figure 1.

Other notable events outside of 2017 were the FDA accelerated approval of Clovis’ Rubraca (rucaparib) for advanced ovarian cancer in December 2016 and the FDA approval of AstraZeneca’s Lynparza (olaparib tablets) for germline BRCA-mutated metastatic breast cancer earlier this month.

Lynparza is the current market-leading PARP inhibitor globally, with reported total sales of $197M in the first nine months of 2017, having snatched up three approvals, two of which were in ovarian cancer and one in breast cancer. To date, all of the drug’s competing agents have one approval at most. The second-to-market drug, Rubraca, was positioned in an earlier line in ovarian cancer and with a broader label in the third line, for germline and/or somatic BRCA-mutated tumors. This temporarily gave Rubraca a competitive edge over Lynparza, which was first approved in the fourth line for germline BRCA-mutated tumors. Rubraca’s competitive advantage did not last, as approval of the third-to-market drug, Tesaro’s Zejula (niraparib), and the label expansion of Lynparza (olaparib)—both in second-line ovarian cancer maintenance, an even broader section— fueled further changes to the US PARP landscape in 2017.

Prominent clinical trial presentations at global oncology conferences in 2017 invigorated optimism for PARP inhibitors. Findings presented at the June 2017 American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) Annual Conference of a Phase III clinical trial in approximately 300 women introduced PARP inhibitors as a novel treatment for breast cancer. Compared with standard chemotherapy, the oral targeted monotherapy Lynparza decreased the chance of progression by 42%, delaying progression by about three months among women with HER2-negative, metastatic breast cancer with a germline BRCA mutation. These robust data, in a setting outside ovarian cancer, hinted at the possibility of future approvals in other indications. Moreover, it provided hope for patients with triple negative breast cancer, a particularly a difficult-to-treat cancer that affects younger women at a higher rate.

Another reason for enthusiasm is that sensitivity to PARP inhibition is broader than previously appreciated, which will increase the already appreciable clinical trial exploration of these agents. Contrary to what was originally thought, the applicability of a PARP inhibitor to non-BRCA cancers is broad, increasing the size of the target patient population. A prominent study published in Nature Medicine showed that up to 22% of all breast tumors carry genetic alterations that render the cancers susceptible to PARP inhibition, rather than 1%–5% as originally thought. In a promising development for patients with non-BRCA mutated cancers, Zejula was approved in March 2017 with a broad label, not requiring a BRCA mutation in second-line ovarian cancer maintenance treatment.

US Tariffs are shifting - will you react or anticipate?

Don’t let policy changes catch you off guard. Stay proactive with real-time data and expert analysis.

By GlobalDataIn a broader context, the impetus gained by PARP inhibitors raises questions regarding whether patients need to go through the toxic hoops of frontline chemotherapies in fields such as ovarian and breast cancer. Instead, provided that the tumor pathology is characterised by BRCA mutations or other similar aberrations, thus rendering them susceptible to PARP inhibition, patients could skip the cytotoxic ordeal of less effective older treatments and go straight to more targeted therapies. In dynamic therapeutic fields such as the PARP inhibitors, the aforementioned paradigm shift could be just around the corner.