Image courtesy Day Donaldson

Discover B2B Marketing That Performs

Combine business intelligence and editorial excellence to reach engaged professionals across 36 leading media platforms.

After three applications to the FDA, ownership by two pharmaceutical companies and one huge lobbying campaign, August 2015 saw the approval of what’s been touted across the media as ‘the female Viagra’. But is the little pink pill’s approval the breakthrough for women that its manufacturer Sprout Pharmaceuticals claims, or do the risks outweigh the benefits for many potential patients?

In August, Sprout Pharmaceuticals’ hypoactive sexual desire disorder (HSDD) drug flibanserin, to be sold as Addyi, was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) after two previous rejections (one after an application by its previous owner Boehringer Ingelheim in 2011 and one after Sprout, which acquired the drug soon after its first rejection, applied for approval again in 2013). Its eventual approval made it the first FDA-approved treatment for sexual desire disorder in either men or women and marked what Sprout describes as “a breakthrough first for women” and “not only an important moment in women’s healthcare, but a societal milestone around women’s sexuality.”

“The approval of flibanserin represents an enormous step forward for the one in ten women living with HSDD, a serious condition with impacts far beyond the bedroom,” says Dr. Lisa Larkin. She is the scientific co-chair of Even the Score, a lobbying campaign set up by Sprout, along with a number of other organisations supporting flibanserin’s approval, which aims to ‘even the score when it comes to treatment of women’s sexual dysfunction’, saying on its website that there are 26 FDA-approved drugs to treat various sexual dysfunctions for men, but still not a single one for women’s most common sexual complaint.

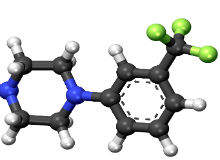

So what is HSDD and how does the little pink pill, which is often compared to Viagra, actually work to treat it? Well, not like Viagra at all, in fact. While Viagra relaxes muscles, increases blood flow to the genitals and should be taken before engaging in sexual activity, flibanserin aims higher, changing women’s brain chemistry and must be taken daily to treat HSDD, which, Sprout says, is caused by an imbalance in serotonin, norepinephrine and dopamine activities in the central nervous system.

US Tariffs are shifting - will you react or anticipate?

Don’t let policy changes catch you off guard. Stay proactive with real-time data and expert analysis.

By GlobalDataThe drug is specifically indicated for the treatment of premenopausal women with acquired, generalised HSDD, characterised by low sexual desire that causes marked distress or interpersonal difficulty and is not due to a co-existing medical or psychiatric condition, problems within a relationship, or the effects of a medication or other drug substance.

Flibanserin: not the only treatment for HSDD

But is HSDD solely a biological condition? While Sprout says yes and cites brain imaging studies which show that HSDD sufferers are wired differently to other women to support its view, according to some experts that’s simply not the case – and here begins the argument against prescribing flibanserin to many women.

“HSDD is a psychological disorder and while that’s not to say there aren’t bio-chemical or hormonal processes involved at all for any women, there’s also a significant psychological, emotional and behavioural component,” says Kristen Carpenter, an assistant professor in the departments of Psychiatry and Behavioral Health, Psychology and Obstetrics and Gynaecology, and director of Women’s Behavioral Health at the Ohio State University’s Wexner Medical Center. “So flibanserin is only addressing one possibility that might be contributing to low sexual desire.”

For this reason, Carpenter is keen to stress that the little pink pill will not be the silver bullet many patients and prescribers might be hoping for. “My biggest concern is that people now think there’s finally an answer to this problem of low libido, but actually there are many answers – it’s just that most of them are not medicinal or surgical,” she explains. “Yes, it’s a large problem and it’s inadequately addressed, but there are many pathways to improve sexual desire, for example psychotherapy for the individual, couples therapy or sex therapy.”

Therapy could even be more cost-effective for patients than flibanserin, as it’s far from clear whether insurers in the US will fork out for the new drug. “I’ve seen estimates that it will cost up to $450 a month, which is a lot of money for people,” Carpenter remarks. “And while therapy is expensive and time-intensive up front, the benefit is more durable.”

Two key concerns: side effects and efficacy

The two other key concerns that have been raised by scientists about flibanserin are its side effect profile – there is a potentially serious interaction between the drug and alcohol – and whether it actually works. During clinical trials, treatment with flibanserin increased the number of satisfying sexual events by less than one per month over placebo.

“The side effects are not trivial and by and large the trials weren’t overwhelming, on top of which, there were many exclusion criteria,” Carpenter says. “Overall, I was not particularly impressed with the risk-benefit ratio and I was quite surprised that the FDA went ahead and approved it. So, I think patients need to understand the state of the science here – we’re not talking about a wonder drug; we’re talking about something that was minimally effective for a subset of people under a fairly constrained set of circumstances.”

Larkin, however, maintains that Sprout’s drug meets – and indeed exceeds – the FDA’s requirements for both safety and efficacy. “Flibanserin has been studied in clinical trials of over 11,000 women and has shown statistically significant effects over placebo on three key measurements: increases in sexual desire (measured by the female sexual function index); decreases in distress (measured by the female sexual distress scale); and increases in the number of satisfying sexual events,” she says, adding that, when it comes to side effects, flibanserin’s clinical trials exceeded FDA requirements for chronic use medications.

Risa Kagan, an obstetrician gynecologist and clinical professor at the University of California, San Francisco, who was an investigator for the clinical trials of flibanserin when the drug was in development as well as consulting with Sprout on its most recent FDA application, agrees. “I was actually somewhat shocked about the extent to which the FDA went when it came to the alcohol interaction issues [asking for extra safety studies], as there are so many other centrally acting agents approved with similar side effects. On the other hand, I say, that’s fine, that’s great – the FDA is trying to be cautious.”

On top of this, Sprout has developed a risk evaluation and mitigation strategy to ensure safe use of the drug, including prescriber and pharmacist certification, and is also conducting enhanced pharmacovigilance and phase 4 studies to further evaluate flibanserin’s risks.

Let the patient decide

Moving forward, it’s going to be absolutely crucial for both doctors and patients to approach this new treatment option with caution – doctors because HSDD is a difficult condition to diagnose, particularly if they haven’t had any previous training in the area, and patients because the side effects are not insignificant and it’s far from certain that flibanserin will work for them.

Fortunately, there is some help at hand, in the form of a presentation created by Sprout that doctors must watch, and pass a test on, before they can prescribe or dispense flibanserin – although Carpenter believes this will only take clinicians with limited training in sexual health so far.

“I hope these materials will also include information about other options for treating HSDD so patients are clear that if medication is something they want to try that it’s not the only thing available to them,” she says. “They also need to know there is a significant side effect profile, the trials themselves included fairly specific kinds of patients and the benefits were modest at best. Of course, if they know all these things and still want to give it a try, they can give it a try.”

Kagan agrees that it should ultimately come down to what the patient wants: “We counsel women day in day out about the risks and benefits of many medications and I think it’s important to leave it to an informed decision-making process and let the patient decide.”

For Carpenter, whether you’re a supporter of flibanserin or not, there is one indisputably positive outcome of the drug’s approval: raised awareness. “What I hope is it results in is better advocacy for patients, better awareness of the multiple kinds of resources that are available, and more comfort among patients with HSDD to feel they can come to their providers and say ‘This is an issue for me, what options are available to me for treatment?'” she concludes.