New research has uncovered a possible link between antibiotic use and the speed of breast cancer growth in mice, and identified an immune cell that could be used to reverse the effect.

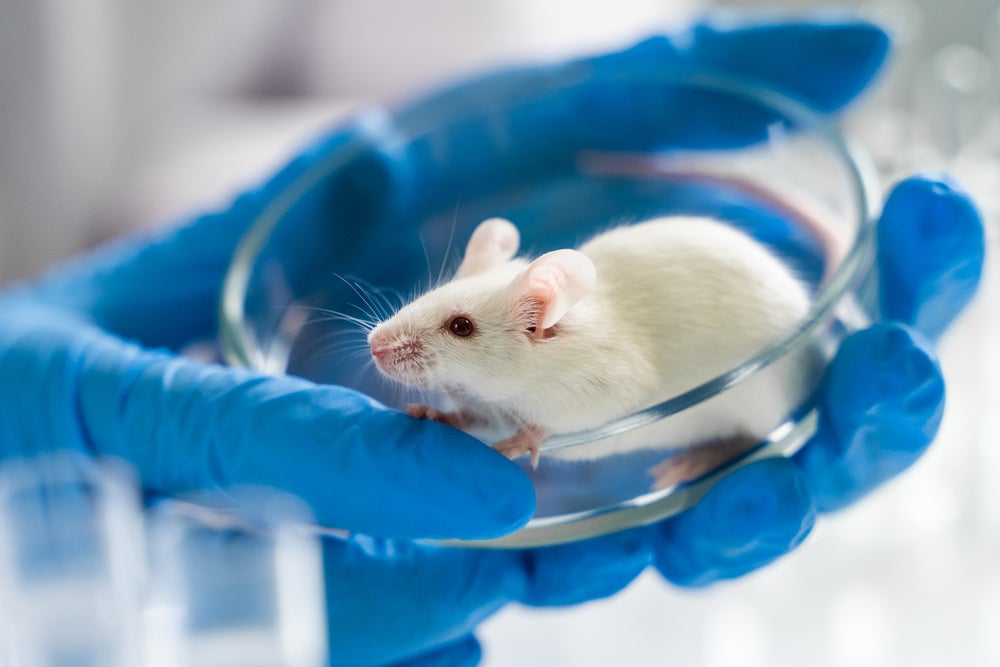

The study, funded by Breast Cancer Now and conducted by scientists from the Quadram Institute and the University of East Anglia (UEA), involved using either a cocktail of five antibiotics, or broad-spectrum antibiotic cefalexin on its own, to understand how disrupting a healthy balance of gut bacteria impacted breast cancer growth in mice.

Discover B2B Marketing That Performs

Combine business intelligence and editorial excellence to reach engaged professionals across 36 leading media platforms.

Researchers found that treating mice with broad-spectrum antibiotics, which led to the loss of beneficial bacterial species, caused their breast cancer tumours to grow faster. The scientists also observed an increase in the size of secondary tumours that grew in other organs when the cancer spread.

The charity-backed study also revealed that mast cells, a type of immune cell, were found in larger numbers in the breast cancer tumours of mice treated with antibiotics. Blocking the function of these cells reversed the effect of antibiotics and reduced the aggressive growth of the tumours, the researchers discovered.

Group leader at the Quadram Institute and research leader at UEA Dr Stephen Robinson said: “With the rise in bacteria resistance to antibiotics we have known for many years that we need to be very careful about clinical antibiotic use.

“Our research has shown that losing ‘good’ bacteria in the gut, as the result of antibiotic use, can lead to an increased rate of breast cancer growth. We believe there is a complex immune element to this mechanism involving mast cells, a type of cell whose role in many cancers is not yet fully understood.

US Tariffs are shifting - will you react or anticipate?

Don’t let policy changes catch you off guard. Stay proactive with real-time data and expert analysis.

By GlobalData“Therefore, future studies will focus on understanding the possible role of these cells as well as looking into the effects of introducing probiotics into the experimental models we use.”

Breast Cancer Now director of research, support and influencing Dr Simon Vincent emphasised that the research is still in the early stages, and has currently only been tested in mice.

“Much more work is needed to understand the complex relationship between gut bacteria and breast cancer,” he said. “However, this research does provide crucial insight and we must now further investigate the effect of antibiotics in breast cancer treatment so that we can find the best way to stop tumours from growing.”